Discovery and Its Discontents:

Managing Library Collections in a Resource Discovery System

“Libraries are more than the customer service departments for corporate database products. For democracy to thrive at global scale, libraries must be able to sustain their historic role in society—owning, preserving, and lending books.”1—Brewster Kahle, Founder of the Internet Public Archive and advocate for the universal access to knowledge.

The modern academic library has no ability to represent collections online, even if it is maintaining a collections approach in its acquisitions practices and workflows. There are no virtual stacks representing bodies of disciplinary and cultural knowledge. The shift from “collections” to “resources” in academic libraries signifies a departure from ACRL Standards for Libraries in Higher Education and what was once considered essential to professional library practice.

For me, and for many people, a good academic library is defined by the quality and experience of its collections, that is, the carefully considered, vibrant presentation of what scholars and educated people in a field, in an academic discipline, think significant, good and important to know. The ability to see what titles experts, scholars and educators think significant is an important part of a library’s appeal to scholars and to intellectually curious people in general. Don’t we want to know what experts and colleagues think is good, significant or worthwhile? Don’t we want to know what is deemed exceptional or relevant by others, what comprises a body of knowledge in a discipline, or at least what other people find “good”? It is through this unique, intellectually-stimulating, content-rich environment that the successful library creates a culture of continuous learning and helps knowledge, especially new knowledge, to become known by others. The experience of collections–not just “access to resources”–is the very essence of academic librarianship, and of what I call “library goodness.” The aesthetic experience of a library as a library is conceptually rooted in the idea of curated collections of texts: their acquisition, their preservation, their arrangement and display.

Collections serve a vital educational function for libraries in that they assist with information-gathering, provide a unique a educational experience, and facilitate our main educational function of making knowledge known. Collections are what people like and remember about a library. Through its collections, libraries create meaning, preserve knowledge for the future and stimulate inquiry in order to facilitate the creation of new knowledge. Collections of scholarly literature and academic / cultural knowledge go hand-in-hand. Collections are comprised of resources, but they are not just passive repositories of “resources.” While resources comprise collections, a library collection is not just an amalgamation of “resources.” The collection, as a collection, is the library’s biggest resource, its greatest service, and what lends it a sense of integrity. Scholarly resources, academic titles in particular, are often perceived to be trivial less outside of a coherent collection. The collection itself, as a collections, has the capacity to add academic value to titles and endows them with meaning.

In the last few years, libraries have gone from imminently visible collections, arrangements of the best titles, carefully considered and preserved for future use, to invisible repositories of third-party subscription content, with titles seemingly selected by no one, and essentially communicating nothing, least of all, a sense of scholarly value, purpose or importance.

Almost by design, no one is paying attention to what new titles are coming in (or not) because titles are now imperceptible. There is no organizational structure or framework: knowledge is now invisible, which should give us reason to question whether this is a functional design for a library. It is all invisible, that is, until someone comes along and performs a search for something. To be honest, no one may be maintaining “the collection” on the backend, acquiring deliberately, strategically, with clearly delineated scopes, in anticipation of use or need, to ensure that there are no significant gaps in our offerings. Any why should they? There is no visibility to any of it. The librarians themselves do not know what is being acquired; they do not need to know anything except how to search for something in those instances someone should come to them with information need. This apparatus we have created may or may not even be a library even by today’s standards, but it surely would not have been thought to constitute one many years ago. What the library has become is a business process fed by other business processes, merely the tail-end of a publisher-aggregator supply chain. Yes, it is highly efficient. But all that is left of the library is a search engine on a webpage which provides remote access to items which reside in vendor repositories. It is entirely automated, and we simply accept this as progress rather than questioning whether this experience is serving our communities well.

This is not a critique of ebooks or of going fully digital, but a critique of our current systems which are optimized for sending users to vendor platforms, rather than seeking to develop a viable and valuable experience of our own in the digital and physical realms. I think it is time we returned to collections as a conceptual framework both for library systems and the user experience in order to create value.

We usually think of our discovery layer as facilitating scholarly access; but from a certain perspective, it is also a barrier to access, limiting what people can see and how titles are displayed. A collection of millions of items can only be viewed ten items at a time. That’s limiting. The user must come along and search for something for anything to be seen. Also limiting. There is no sense of the size or extent of the collections that is there. Another limitation. There is no objectivity, organization by what is relevant to the discipline by topics, only of what might be relevant to the user. This is a very significant limitation in an academic environment. Yet, the experience of e-resource discovery (that is, search) has now become the basis of the library experience online. No one really questions this e-resource discovery model of the academic library very much. We do not seem to expect that academic libraries do anything beyond providing access to third-party resources. But libraries were always about access to knowledge, to whole collections and not to discrete resources.

What impact has this transformation of the academic library, this abandonment of academic standards for collections and collection development, this commodification, had on learning? How has it impacted education and the business objectives of the library and the university?

Engagement with a good library collection has always—at least until recently—been regarded as an important part of the education of university students and promoting intellectual life at a university. Collections were also previously considered to be the foundation for a curriculum, vital for new course development, necessary for knowledge transmission, a central part of the college library experience and what made the library appealing to users. The experience was memorable. Time spent in the library exploring and discovering interesting things often brings back fond memories for alumni. The library and/or collection still symbolizes the academic commitments of the university to scholarship; but titles on display serve more than just a symbolic function. It draws people in. Even today, a visit to the library is often a first stop for prospective students touring campus or contemplating a return to graduate school. What are they hoping to see? Previously, prospective students would engage with the collection often in order to clarify their own level of interest or commitment to academic pursuits and to make judgement as to how good the library is. Students may form anchors to the university through the library’s collections even when the course offerings at the school fail to affirm their academic interests or educational objectives. Collections seem to validate people and their interests in a way that “access to resources” through a search box does not.

We often describe collectionlessness in glowing terms as “going fully digital,” but what is online the opportunity for a user to discover resources for himself, whatever resources the library or its vendors offer, through a search box known as a “discovery layer.” Unfortunately, users soon discover that by going directly to vendor sites, they are provided with a superior search experience than what the library can offer through its discovery layer. It often falls into disuse.

This alone should make us rethink our current designs and priorities in the academic library.

What I write about is not a defense of print or a critique of discovery, but rather a defense of library collections, both as a conceptual knowledge framework and as a basis for a positive aesthetic user experience of a library. It should be the basis for our interfaces, or an optional interface. I will argue that libraries are fundamentally intentional collections of intellectual and cultural objects, regardless of format. We should be primarily about “titles,” scholarly works and cultural objects in context, and only secondarily about commercial products. We should be about our brand, and not so much about our vendors’ brands.

Collections should continue serve as the foundation for an academic library’s content strategy.

The library should be able to organize all and/or a subset of its titles into collections, per library standards and best practices. Print should not be treated one way and digital another in an integrated library system. All titles, book, ebook, journal, ejournal, should be capable of being organized and browsed according to the way the disciplines and the topics within it are organized.

Collections of titles organized according to the priorities of the disciplines (how the field is organized, the topics and sources it deems important) possess intellectual value and intentionality. Collections lend credibility to the library as a service, generate interest, and are an important form of scholarly communication. Collections presuppose shared value and have the capacity to express and create value, to the extent that a title by itself or placed next to other random scholarly titles are fairly trivial. It is only when placed into a collection in context with similarly scoped works that its scholarly value becomes apparent to other scholars. This is why librarians were previously taught that the proper way to weed is to go to the shelves. Librarianship is not about access to books or resources, but about access to collections maintained with consistency and care over time.

Access to resources, on the other hand, provides no intellectual value beyond access to the resources themselves.

Right now, library “resources” are online. But library collections, as collections, are not online.

I believe this is a shortcoming of academic library systems, which have eliminated browsing and display by classification, even though academic library standards still oddly center around the provision of collections, not just to “discoverable resources.” ACRL Standards for Libraries in Higher Education states, for example, that academic libraries “maintain collections that incorporate resources in a variety of formats” and preserved over time (5.5.2-5.5.4).2 Collections conceptualized as the umbrella, the organizing principle for a library and its resources.

It would be easy to argue that with the state of search technology today, collections are no longer needed, since people can pretty much find what they want online.

But what if the information I am seeking is knowledge of the publishing activity in my field? What if I want to know what are the core journals and books in my field? What if I want to see what new titles have come into the library organized by topic? Our systems should facilitate these kinds of experiences, too.

Search is a wonderful tool which fills an important need. But the experience of authoritative collections should continue to remain the overarching intellectual, organizational and conceptual framework for an academic research library, our cornerstone, the construct which drives acquisitions, assessment, marketing and display.

The library should be fully online; but to be fully online, we need the organization and representation of academic knowledge which comes only from classification and content curation. It is through classification and display that we help to make academic knowledge known fulfill our education mission. Arrangement by topic is an important way that the intellectual strengths and weaknesses of a library can be assessed from an academic perspective.

Why Collections are a “Business Requirement” for the Academic Library.

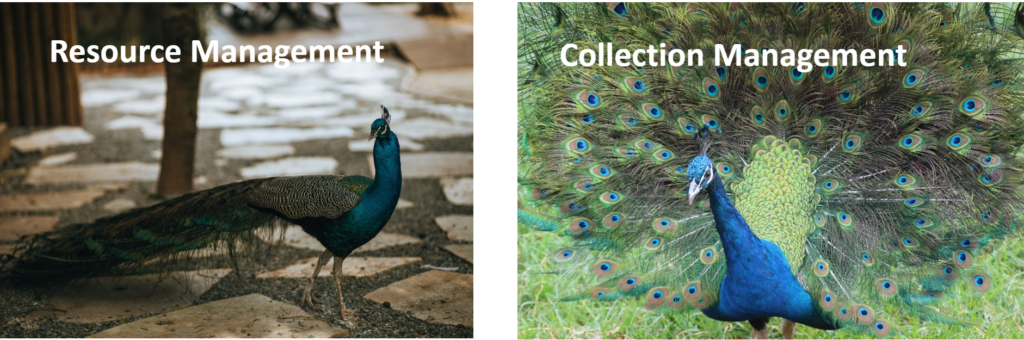

Collection management is an intellectual, academically-rigorous framework for the the selection, classification, organization, description, evaluation and display (user interface) of bibliographic resources. It is not synonymous with managing print formats, even though print formats were historically organized and managed as collections.

A collections approach is a conceptual knowledge framework for ensuring quality and integrity and a good user experience of a library. Collection Management is an important part of the core curriculum for an ALA-accredited master’s degree. Without the conceptual knowledge framework of collections, the library’s content becomes vendor-driven, lacking in integrity. Arguably, the user experience suffers from this hands off approach to collection management. A decision is made to abandon collections. No need to bother keeping up with what is coming out or what is new. It is more efficient this way.

When most people conceive of collections, they think of the bookshelves of the library, which we call “the stacks.” Traditionally, the purpose of the catalog and our metadata was to get the user to a location in the stacks, where he could retrieve his item and also browse related items. However, the collection itself was the basis for the intellectual and aesthetic experience of the library and was an importance access point, increasing the likelihood the item would be seen. If the collection was consistently good, it engendered trust. After a few encounters with a collection, scholars determined whether or not they could rely upon it to have what they might need in the future.

Print collections added value in the following ways:

- It encouraged browsing. It stimulated new interests, exposing students and faculty to things they did not know about and would not have thought to look for.

- Served a symbolic function, conveying the worth of education, that scholarship is worth investing in, the same academic commitment we want students to possess to stay in school and pursue higher education.

- Helped librarians to identify gaps in the collection and ensure that it was current and balanced.

- Provided for transparency, so users could see that the library had and could predict what it would have in the future.

- Kept faculty and students informed about trends in publishing in their field.

Just as art museums are not just about “access to art,” the library is not primarily about “access to” resources or intellectual objects, but about the experience which is supported by collections as a whole, the organization, preservation and perpetuation of knowledge.

The invisible library is an ineffective library. The invisible library does not encourage intellectual curiosity or learning.

The invisible library contributes to uninteresting and unwelcoming spaces.

What almost all academic libraries today have done is to put a kind of meta-search engine on subscription databases to replace the online public access catalog (OPAC), the stacks, and the need for librarians to manage their collections. They have eliminated collections, both print books along with the conceptual knowledge framework of collections needed to ensure academic rigor, and which might have been replicated online. I believe it was to our vendors’ advantage to eliminate the very tools which allow academic librarians to manage content and to know what they were acquiring.

Catalogers have all but disappeared, along with many other Technical Services functions. Access to vendor products is achieved through APIs and integration profiles. There is some troubleshooting which arises from time to time, but the resolution more often than not entails opening a ticket with the vendor.

Librarians have been replaced not just by automation, but also a shift in responsibility for collection management and title selection to vendors. We buy what they publish and they like it that way. A publisher-aggregator pipeline now determines most of what we acquire. We are the tail-end of their supply chain, and through this business model quality may suffer.

EBSCO’s Literature collection has no literature in it, just secondary sources. Often when it comes to ebooks, what we license through aggregator packages is oddball stuff we would never have acquired outside of a package. E-resources cannot be represented as a collection, arranged according to our rules and standards for display. All we get out of the millions we spend is a search box through which people can discover content for themselves or be incentivized to go to vendor product platforms to do research.

Like big-box retail stores, the academic library is now largely a vendor concession, and like the word “concession,” we have been forced to make them in order to honor our license agreements with vendors and better enable them to better monetize their content. Eliminating collections is itself one major concession, perhaps impacting some disciplines more than others; but ultimately affecting everyone, and certainly impacting the future of libraries. Now, no one but the vendor, who charges increasingly more for access each year, will select and preserve content for the future, and what we acquire (license) will remain invisible through our user interfaces except when someone comes along with an information need or assignment. The experience we offer is limited by the fact that the metadata needed to design good bibliographic interfaces is being phased out by vendors.

We have also made a concession in terms of our bibliographic metadata, which in turn limits our user interfaces. Vendors cannot be expected to populate library-centric fields, LC Classification and LC Subject Headings of “discovery records,” and why should they? The only purpose of metadata from the vendor’s perspective is to drive library users to their platforms, not to enhance the search experience on the library-side.

We have made concessions in terms of access and resource sharing. The profit of vendors is threatened by resource sharing so naturally, they have sought to restrict it. The result is that the unaffiliated researcher may experience difficulties continuing his research after he graduates; a doctor may not be able to access libraries of clinical medical research. The engineer cannot develop innovative solutions without access to a good engineering library.

Many in my field continue to believe these changes made in recent years to be progress. On some level, it is, of course. It is more efficient leaving everything up to vendors and telling students that they should use this or that vendor platform, should they have an information need not satisfied by Googling. While this might add some small value, this does not fulfill the mission of a library.

Scholars want and need to see new titles and core in their field of study, both what is coming out and what the library is acquiring, and we should be able to put titles into public view if we want to encourage engagement with them.

Visibility is the root of the word “respect,” for it means to put something into view where it can be seen (“spect”) and considered again and again (“re”). To show respect something means, literally, to put it in front of others where it can be seen again and again. The library shows respect for titles by acquiring them and putting them into view.

In this digital age, I believe we must do more to be good as a library than provide passive access to invisible subscription content, that is, provide access to indexed records which live in an invisible repository linked to items that live temporarily on third-party platforms, and which are accessible only to those with current institutional affiliation. We must be more than a federated search tool.

Rather than trying to do more to encourage awareness and engagement with publications and raise literacy levels (in higher education, “literacy” means not reading fluency, but knowledge of the authorities, sources and publications in a field and familiarity with ideas and trends), and doing more to make the library a more intellectually stimulating and immersive experience, a kind of malaise has set in in which we are content to be a federated search app on subscribed content.

Librarianship is becoming further insulated also from complementary technologies, techniques and platforms—even museums and ecommerce sites—which could help us to be more effective at conveying ideas, scholarly content and knowledge. Rather than attending ALA Conferences, some of us should be going to SIGGRAPH (IEEE) (conference for computer graphics and interactive digital technologies) and learning to make our spaces more interactive, immersive and dynamic, as many museums have done.

A walk through the library should be an educational and immersive experience, changing from week to week, using technology to facilitate awareness of new titles and research activity. It should promote resource use.

That is what technology could and should do for the academic library. The library must strive to reflect scholarly communication in the disciplines, not be a stagnant space void of content. It should be a window onto the world of scholarship, not literally “a window.”

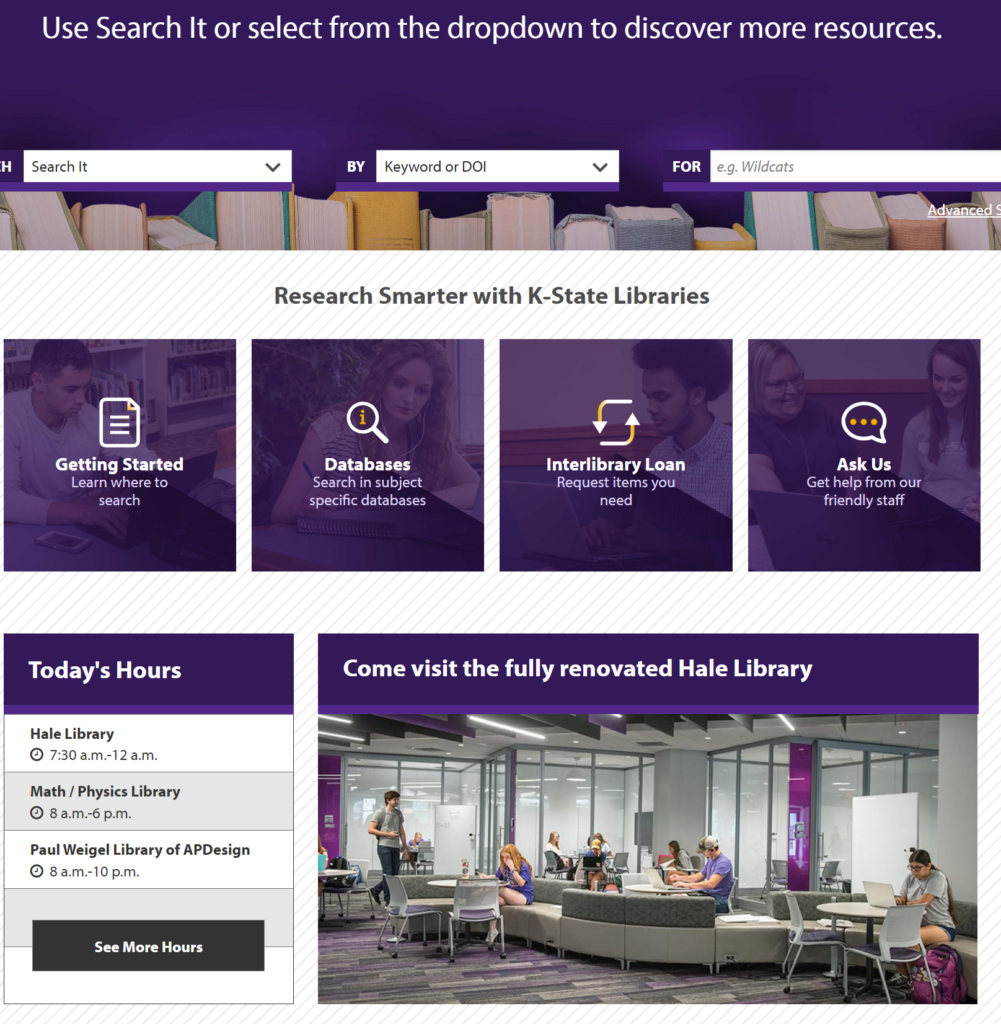

We should borrow from digital marketing to revamp our websites from what they have become, a static page with a search box as its centerpiece, to something much more layered, content-driven, immersive and personalized.

The modern library needs to be more attuned to presenting ideas, concepts, technologies, current trends and scholarly literature on which these may be grounded. For example, through interaction projection technologies, it would be possible to present specialized digital collections and virtual periodicals racks in the departments. Why would you want this if scholarly can jump on their laptops? Because putting current journals in front of people, not just making things discoverable, is or should be an objective in itself of libraries.

Putting things into public view creates a sense of value around it, another function of a good academic library.

The academic library must renew its commitment to collections, if not in print, than through online platforms designed to support the representation of virtual collections.

Instead, librarians continue to eliminate collections, both the stacks of books and a “collections approach” to acquisitions, subscribing only to gigantic packages and claim that this is “progress in our field.” We continue to erode our bibliographic standards. No one, not even those who work in the library, is aware what titles we have or do not have. Is the library experience we wish to support just a search box, an A-Z list of databases, and some LibGuides?

Such is the new academic librarianship, in which we are able to really do only one thing, which is to embrace our inevitable commodification and absorption by large vendors so that very soon, Clarivate ProQuest Ex Libris can offer a one-stop library research solution to the university.

Collections are resistance to commodification.

It is through collections, arranged and organized as collections, that knowledge is formed, preserved and communicated to scholars as knowledge, as a consensus as to what is good and important to know. Collections are a catalyst for learning because they convey to people what they do not know and would not think to search for. Especially at large universities, collections serve a more important function than people may realize. It is sometimes said that it can take up to 200 years for theoretical knowledge to become applied. What happens when institutions once dedicated to the preservation of knowledge are no more, or become commercial entities? Knowledge is lost.

A commitment to collections often comes with a commitment to academics and disciplinary knowledge, a commitment to public access and resource sharing, a commitment to preserving the unique culture of the school (if it has a reputation or institutional identity), a commitment to publication (because visible collections are form of respect for scholarship), and a commitment to life-long-learning, all of which are jeopardized by the library’s recent commodification.

Library collections are selective, intentional, deliberate, purposeful, and a form of scholarly communication about scholarly communication. As a form of scholarly communication, it must be public or visible to communicate. Obviously, they cannot communicate if our resources are not visible, random aggregations and unintentional. A collection is created and maintained by librarians and scholars, not by corporations who profit from monetizing their content.

A good collection, a collection that organized, current, and cared for consistently over the years provides intellectual value and aesthetic appeal to educated audiences who can appreciate it for what it is. By the time students graduate, students should have received an education at the university such that they are familiar with the core titles in their field. These are typical organizational objectives of the library. Library designs are not helping us to achieve these educational objectives. They are merely helping vendors to monetize their content more effectively.

Collections are necessary to support a vibrant library experience and to support higher education. They are a source of inspiration and knowledge. At a university, collections should inform the curriculum, refreshing and reinforcing instruction.

A search box doesn’t do that.

The Visible Library:

Resource Visibility & Public Access increases Discoverability.

Collections are the product of librarians and scholars, a representation of the scholarly activity in the disciplines within clearly defined scopes, consisting of what experts and educated people believe significant, worthwhile and important to know.

Collections are not just random resources, even random “relevant” resources in a publisher’s inventory.

They are the best resources, within clearly defined scopes, for a particular audience. That is what we have been taught, at any rate.

They are also not what the librarian judges to be good, but what experts in the field judge to be good. Collections operate on a meta-level of bibliography: they are deliberate arrangements of titles reflecting, or approximating, the organization of academic knowledge in the disciplines.

Collections enhance the scholarly value of the resource contained within them. They operate at the “title” level, the bibliographic level, not at the vendor package level. With collections, titles are visible as part of a collection, visibly organized and systematically arranged, rather than being merely retrievable content.

Collections were once said to be our most important service of the library. Visibly displayed in meaningful arrangements, library collections signify academic achievement as a value and knowledge as a priority.

The collection as a whole tells a story and has narrative value, as do all good collections. Collections presuppose relationships, connections and intentionality. “Collections” support broadest possible access, even by people who know nothing about it, resource visibility, resource sharing, knowledge formation, public access and life-long learning.

“Resources” on the other hand, are simply, well, entitlements which support institutional access to information for the year in which the resource was licensed, and there is no commitment made by the library to preservation, resource sharing, public access, display or life-long learning. There is no commitment made to the organization or formation of knowledge, only immediate access to third-party content. Access to collections and access to resources are not the same thing.

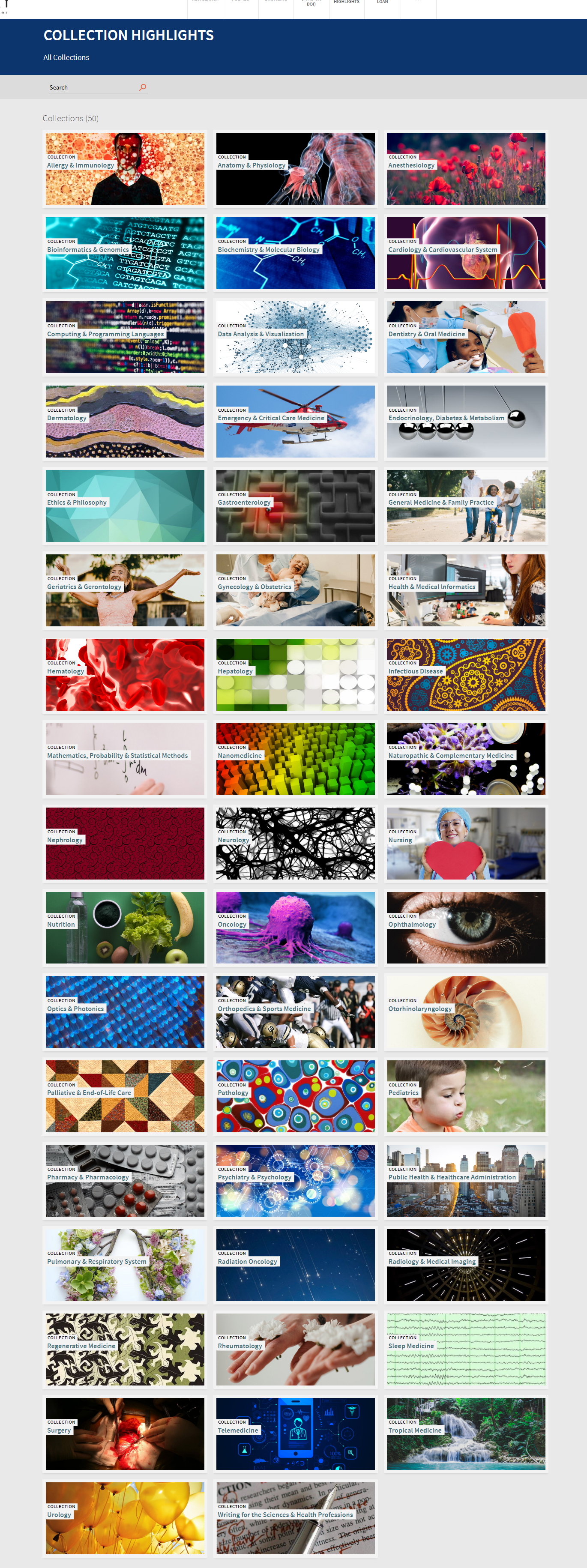

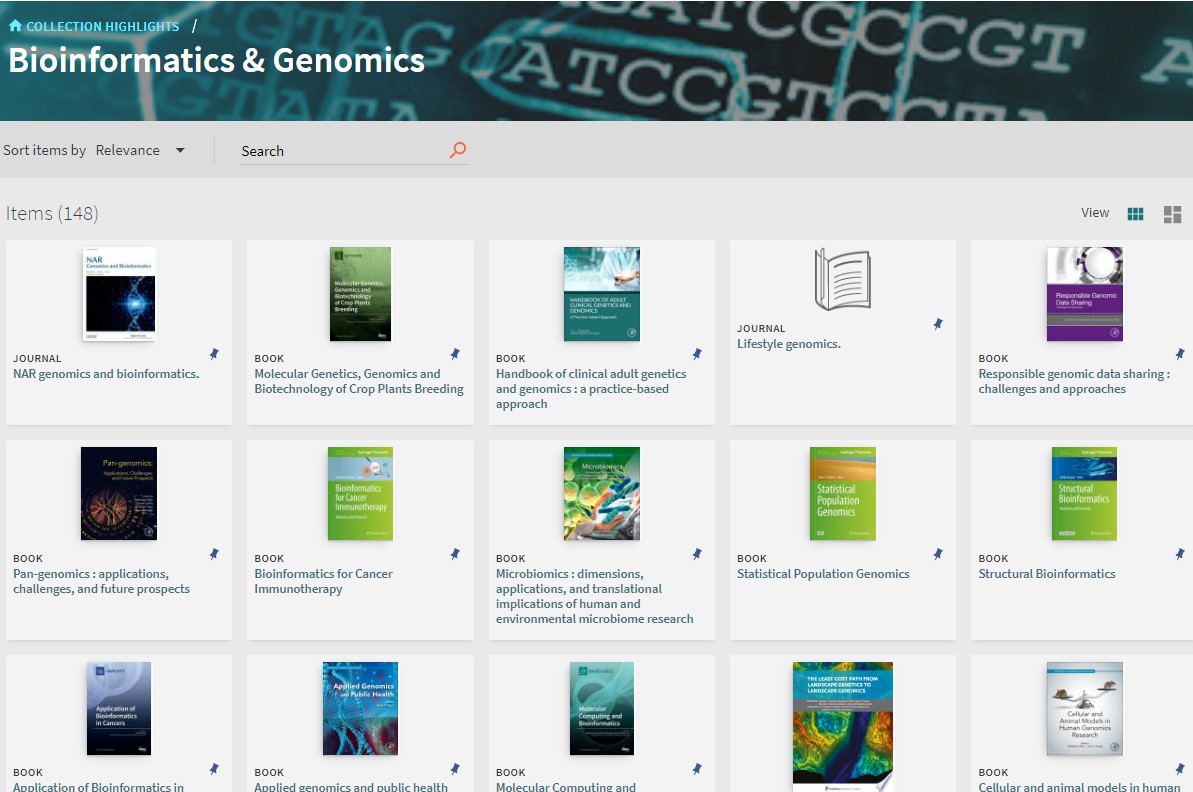

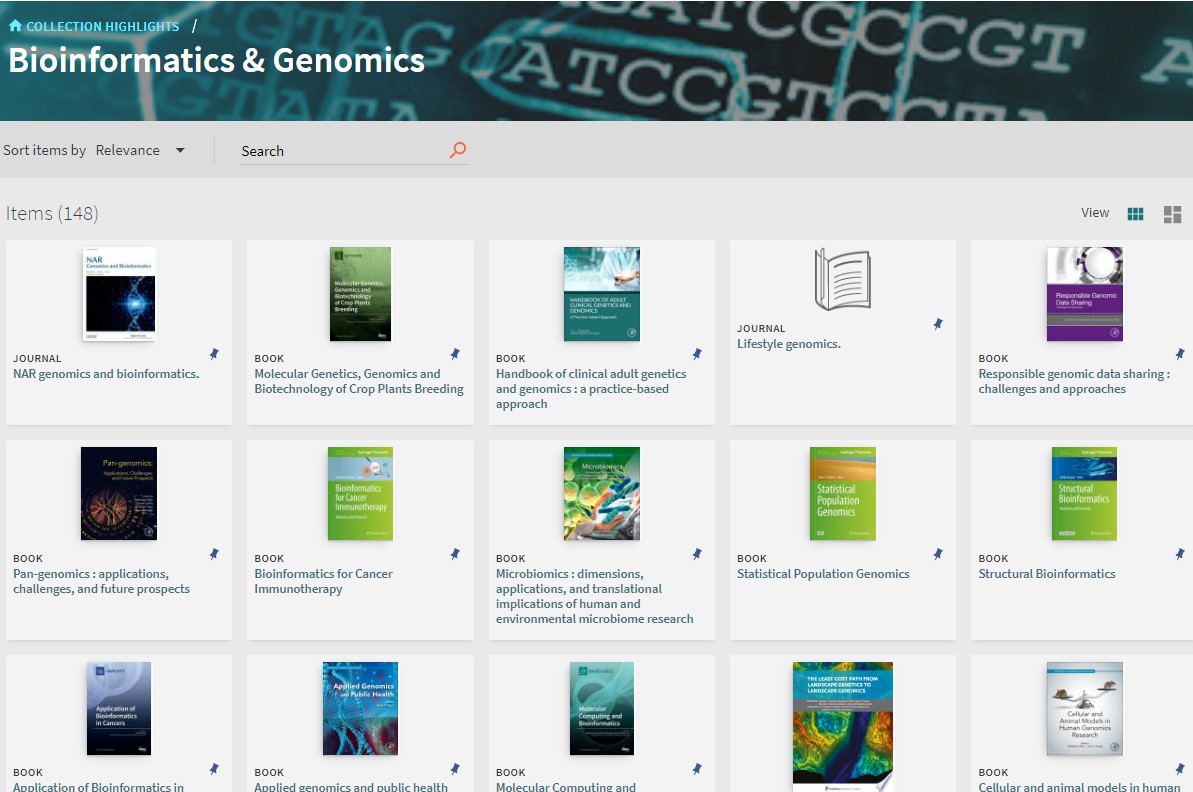

Today, whether one works with Alma Primo, OCLC WMS, or any other academic library system, e-resource discovery is the new paradigm for the academic library, replacing our former bibliographic systems, and this may be the sole basis for acquisitions and the user experience of the modern library outside of some research guides we might create. There is no integrated “shelf-list” function, for example, for all of the titles we acquire through license agreements to make this work the way it should or might. I have 100,000 ebooks from EBSCO, 100,000 from ProQuest, 100,000 from Taylor & Francis, 50 from SAGE, 50 from McGraw Hill and about 1,300 more from other vendors. I have thousands of journal titles and videos and ebooks from 100 different vendors, and perhaps some books and videos as well.

But I cannot put them all together to form anything like a browsable collection online, or pull them together by discipline and specialty for reporting, and I really cannot identify collection gaps easily. I don’t know if “the collection” is good because there is no “collection” there to be systematically assessed, as we were trained to do.

So much for the organization of knowledge, which ACRL still seems to still think important for academic libraries, even if our system designers don’t. Yes, the “organization of knowledge” is still part of the ACRL Standard for Libraries in Higher Education. How do we support that in an e-resource discovery system? So much for stimulating intellectual inquiry, which is hard to do without visible collections. There is no bibliographic control in e-resource discovery systems. There is no shelf-list, no possibility for a conspectus analysis, which was at one time considered a standard collection development tool and best practice by IFLA3 and all medium to large academic libraries.

More than that, I cannot curate and present content to my faculty and students in their subject areas very effectively. The metadata isn’t there. It could be, it ought to be, it was, but now it isn’t. It isn’t going to be, either, because during COVID, vendors conspired to replace our MARC bibliographic standard with their own publisher-driven NISO standard,4 which makes all that LC stuff in our bibliographic record optional. They are not bib records, they are discovery records.

Through discovery alone, we have simply become one with our vendors. There is no distinction between what we offer and their inventories. Only, as we all know, and they know, search works better on their side than our side, because the metadata they give us is often poor, the algorithms they use on their platforms are better, and theirs searches full-text, which ours do not do.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t offer discovery, but that this should not be our everything. It is a limited conception for the whole of an academic library, and compared to some of the citation discovery engines we had in 2007, like Grokker, it isn’t even all that advanced. Grokker did dynamic clustering and labeling on the fly and could present a browsable overview of everything in real time: Primo, the indexed-based search on vendor-provided metadata, can’t do that.

We need a systematic overview like we used to have in order to manage and present a collection of titles, even an electronic “collection.” Despite what they may call themselves, vendor packages are not electronic collections, they are just aggregations of digitized content vendors license to us. “Resources” in today’s parlance are merely vendor entitlements, commercial products. Academic library standards are not about managing vendor entitlements, but selecting titles and forming them into collections.

And why should I need to spend time searching this and that topic to get an overview of what I have in a subject area for program accreditation (“What are all the ebooks and ejournals you have to support this program?”), rather than viewing a comprehensive report of all that I have by discipline, subdiscipline, class, and topic, down the LCC hierarchy from general to specific, down to the cutter number and finally the year of publication?

LCC is not a strictly alphanumeric number, and it sometimes has two decimal points which tends to throw off Access and Excel (They can handle two letters, as some of our classes have. . . but two decimals breaks it). However, there are sorting routines out there for the Library of Congress Classification which can be used for comprehensive reports like this. There is no excuse for its absence from our modern library systems (The 050 field, the LCC number, would be an obvious choice, since e-resources do not have call numbers assigned to them; their bib record contains the LCC number for their print equivalent).

We must have ways to make our content visible to say, “Here all that we acquired this week/month/year to support your program,” which is also dependent on LCC (really, a conspectus report based on LCC).

This is only possible with a collections approach. Collections, even virtual ones, are what librarianship is all about, not just “access to.”

What’s the Use of Collections?

Academic libraries are about the organization, perpetuation and creation of disciplinary and cultural knowledge.

We have traditionally done this not though print or books, but through collections. Collections are a philosophical construct that are more than the sum of its parts. It is bibliography, a form of scholarly communication. Each item in a collection is related to other items in the collection. Collections are logical, intentional.

A resource discovery model, on the other hand, presumes an item has no intrinsic value apart from its relevance to the user’s query.

If they have an analog, it is to what was once referred to as a “learning resource center,” or LRC.

Of course, academic librarians cannot possibly acquire title-by-title today and keep up with the volume of publishing activity that goes on today. But is it expecting too much of our library service platforms for a library to be able to identify all of the titles it currently acquires and then form these into virtual visible collections, so we can fill the gaps and spin off title lists to be able to make our content more visible?

If people at the university are there to obtain knowledge, it seems not unreasonable to me that the university library provide some reliable and consistent mechanism for efficiently communicating to users what constitutes disciplinary and cultural knowledge in the first place, what is in their collections, presenting the best and current titles for that audience, arranged for maximum visibility, impact and appeal according to the priorities, topics and organization of the academic disciplines. These are, or form, bodies of knowledge.

Collections are academically-rigorous bodies of knowledge, not an assemblage of commercial products. Ideally, this knowledge should belong to everyone. It is a cultural asset.

This is a fundamental premise of the academic library, now jeopardized by commodification.

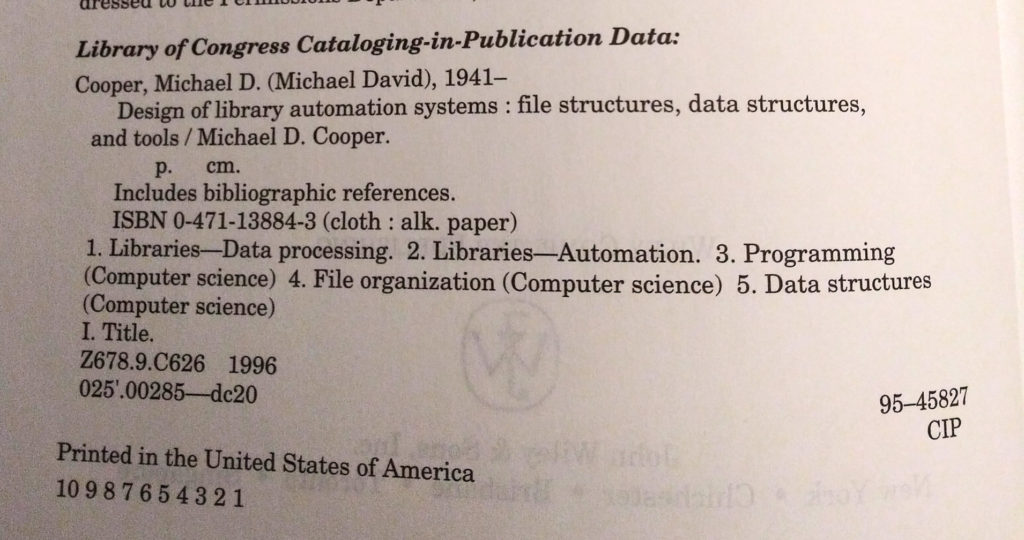

Collections can assume any format, including hybrid or online. A collection is in large part as intellectual construct, a way of cataloging, a way of organizing, a way describing, a way of presenting and visualizing bibliographic content in relation to the academic disciplines. Placing an intellectual work into a broader intellectual and cultural context through bibliographic description and metadata was always our function, not just “access to” the thing itself.

This ideal for arranging, conveying and learning the knowledge through scopes or classes goes back to ancient philosophy. It was referred to as topoi (topics) by the Greeks and loci (places) by Latin authors; we may call them topics or “scopes.” In my profession, visible collections, the ability to browse by topic, is considered an important access point which has disappeared from many libraries as they have gone online. Through their library, students and faculty should be entitled not just to access resources, but to access disciplinary knowledge itself, to come to what other educated people are discussing and engaging with, so they can become and remain educated people. Our systems should support this type of engagement and use. What do I mean?

Business requirement: People at a university should be made aware of new books and articles coming out in their areas of interest through the library.

Business requirement: People should be able to browse titles in topical arrangements mapped to their disciplines.

Technical (Functional) requirement: The 050 is a required field and academic library systems must support sorting and arrangement by LCC.

Support for intellectual inquiry is our job, the mission of the library, not just to provide access to vendor products.

With visible collections, disciplinary and cultural knowledge is more likely to become known, seen, preserved and appreciated by current and future generations of students and scholars.

Maintaining collections is an important part of our educational mission at any university, in any academic setting. Unfortunately, I see academic libraries as becoming one with large commercial content aggregators at this time, which does not bode well either for the future of academic librarianship.

We must advocate for our spaces and our systems to be content-rich learning environments built around library standards and library-centric priorities like “resource use.”

Maintaining Library Collections are in the Interest of the Community.

As a profession, we should openly debate the ethics, limitations and impact of an acquisitions model done entirely through license agreements with vendors, whose content is made available in the library only in discovery or through links to the databases. We must have carefully considered business requirements of our own, with projects, goals and objectives flowing from it.

The academic library must ask itself:

- Why spend millions of dollars on titles that are practically invisible inside of the library and on our own platforms?

- Why spend tens of thousands on library systems that cannot manage academic library collections?

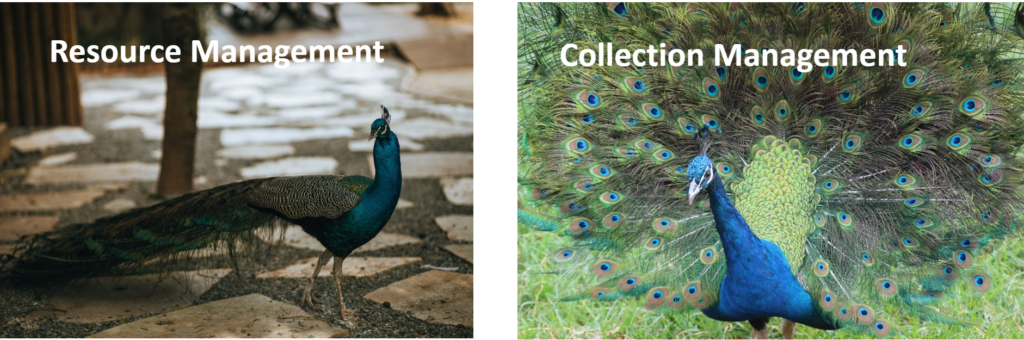

Collection management is not the same thing as, say, merely providing an efficient tool for providing access to third-party licensed content through a search app, or for retrieving some relevant resources in response to a query, should someone come along and have a need to know something. Collection management is not acquiring in an ad hoc manner, “just because” there are funds left over at the end of the year, or acquiring just when someone comes along and requests something. Collection management is an academically-rigorous, scholarly practice in libraries where librarians are charged with ethically and impartially selecting, managing, describing, organizing, arranging and presenting scholarly content for the benefit of scholars and a larger community in anticipation of use and need.

Collection management often entails consulting bibliographic tools and review sources. Title selectors are also charged with knowing about the collection and the discipline, as well as the interests of the students and faculty to support them. They are charged with managing a budget conservatively, so that funds are always available throughout the year to acquire when new books come out or when faculty request titles or resources to support either their classes or their own scholarly research interests.

“Resource management,” in the other hand, is a commercially-driven model in which our vendors, content aggregators and large publishers platforms determine the academic library’s content, who is entitled to access content, and under what circumstances.

Resource management is the library becoming the “tail-end of the publisher-aggregator supply chain.” It is a commodified model. The library profession should refer to it in these terms, as the commodification of librarianship.

We pay an annual licensing fee for them to select and manage content for us and manage our (now their) metadata. Where we used to strive for vendor neutrality, now we acquire whole product lines (say Oxford) while excluding other potentially important sources of information (say Cambridge). Where collection management presupposes our goal is broad access to scholarly publications to further scholarship, knowledge and the public good, resource management reinforces the idea that the library’s mission is to provide access to commercial products to benefit only those with institutional affiliation, even though the library may have an obligation to serve the public.

Many libraries transitioned from collection management to resource management in the years leading up to and following COVID, when they transitioned to being fully digital and repurposing its space into a lounge. During that time, I left one library, once a comprehensive academic library which had become a learning center, down to about three full-time librarians (a Director, Associate Director, a Weekend/ Evening Librarian, and me) from fifteen. When anyone left, so did their positions.

I left there to work for another area library which permitted remote work for that year. Shortly before I started, however, that library went in the same direction as the library I had just left. It eliminated collections and roles, and underwent major renovation to being a reading room/ study hall.

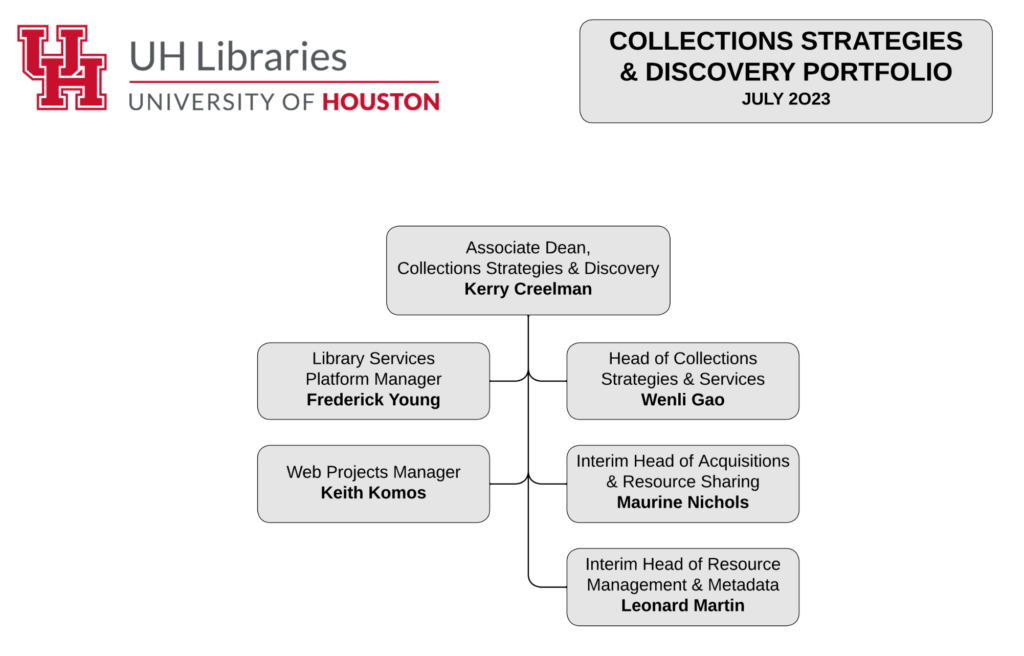

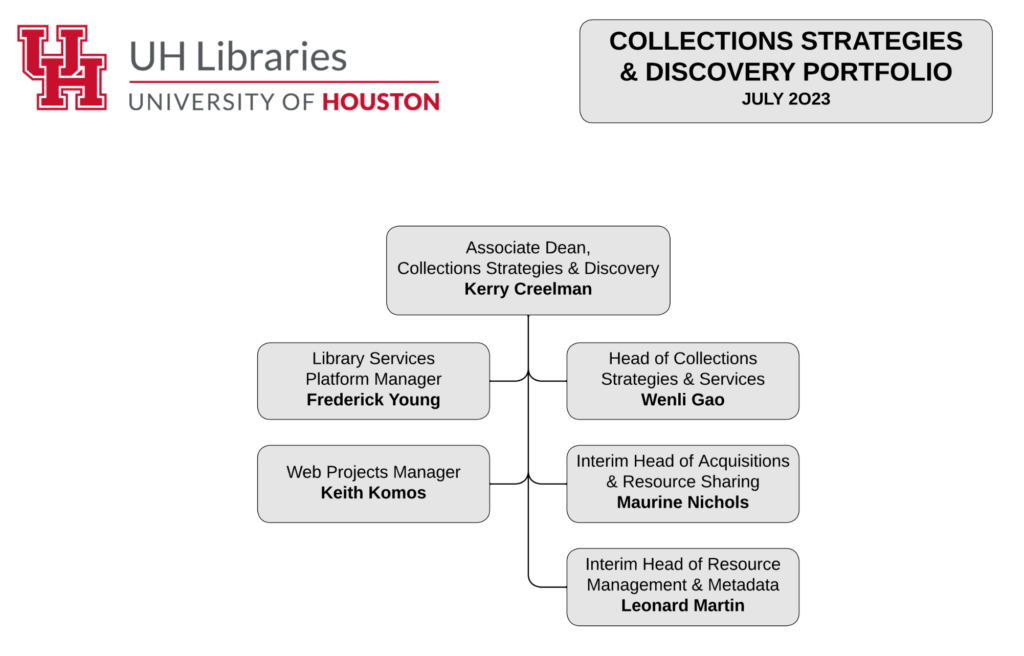

After deciding it would go collectionless, the University of Houston Library System reorganized in 2023 as part of a new strategic plan and renamed its department responsible for technical services, metadata and acquisitions “Collections Strategies and Discovery Services,” putting collections back into the name and job functions of its librarians. It also put Web Projects Manager also under this department, another inventive and brilliant idea. We should be thinking of the online library as a platform and as a destination, not as a search portal on a static page controlled by another department.

The University of Houston Library System also expresses commitment to life-long learning by allowing public access to its electronic resources, which is the correct approach. It describes itself online as a public research institution, which of course, it is. All libraries attached to State-supported institutions are “public” research libraries, to be open and fully accessible to the public, according to our State mandate. The public academic library and libraries of clinal medical research which receive public funding exist for the public good and life-long learning.

As academic and medical libraries are increasingly seen not to consist of collections of titles which support life-long learning and future scholarship, but of entitlement of packages licensed only for institutional access for students and faculty for that academic year, our former commitment to public access, to collections, and to resource sharing, has eroded.

As libraries have become vendor resources, corporate entities, they have also become more ambivalent about their obligations to serve the public or share resources with them. When I say “the public,” I mean everyone in the community desiring access to academic resources, including those no longer enrolled in school there. They can be alumni, professionals, researchers, people with doctorates, other students, visiting scholars, retired faculty. At one time, we welcomed them with open arms, even had community outreach librarians, but not so much these days. This trend in academic libraries can be correlated with collectionlessness. As we no longer own our resources, we are no longer entitled to share them.

Like the differences in professional practice between resource management and collection management, these are deeply philosophical questions which strike at the very heart of the definition of professional librarianship today. For accreditation review, no one is asking:

- How are you ensuring that you are offering students the best content?

- How are you ensuring that students actually see what you are acquiring for them?

- How do you collaborate with faculty on collection development?

Maybe they ought to be.

As we have moved further away from acquiring title-by-title as an ideal and actually managing library collections, the intellectual work which attracted many of us to the profession may no longer be part of the job. But my belief is that this lack of knowledge and lack of commitment to it is contributing to the library’s irrelevance.

These days:

- No one inside of the library may be expected to follow or keep up with the scholarly literature or publishing, a consequence of being only about the retrieval of resources on vendor platforms.

- Collections are now associated even by most of my colleagues with the print era or a kind of leisurely activity known as “browsing,” rather than browsing functioning as an important form of scholarly information-gathering and learning in a college or university setting.

- There is seemingly no association by decision-makers between the curriculum or quality of instruction at the school and the library’s collection.

- For an academic library collection to be a “collection,” it must be arranged or organized as a collection to reflect the disciplines. Even if a university is maintaining collections in terms of acquisitions practices, collections are just “resources” without being able to be arranged so they can be experienced as a collection.

- Arrangement is an important aspect of properly managing the user experience of intellectual and cultural objects in both libraries and museums. However, our e-resource discovery systems do not support arrangement of titles by classification.

- Collaborative collection development, where we present new and forthcoming titles to all of the faculty and allow them to participate in the acquisitions process, is no longer standard practice, even though there are tools (like ALA Choice) to facilitate this. Through collaborative collection development, we kept faculty up to date on new titles in their field, not just new products.

- Even at the largest universities, there my be no acquisition of new resources in anticipation of use and need. This was always a hallmark of good libraries, that faculty could count on the library to have items in advance of need to keep their knowledge current.

- Even in the largest university libraries, there may be no thought of preserving items for the future. The lack of commitment to collections is a lack of commitment or ambivalence toward scholarship.

- The IT Department may now be managing our authentication services and website for us, indirectly influencing access policies and leaving the online library able to communicate with users only in the most oblique ways.

- “Acquisitions” is also fully automated in many libraries, or as much as it can be, managed by vendors, outsourced. This arrangement helps publishers to better monetize their content, but leads to vendor bias and restricted access of content worthy of inclusion in a good library collection.

- Where we used to envision ourselves as positive “agents of change,” now no one even sees what we acquire. If they do, no one thinks it was placed their by anyone locally.

- Where before we railed against being perceived as a study hall, many of us are talking about our “innovative workspaces,” a space which to be honest resembles any other building on campus with places to sit and study. Nothing of intellectual interest may meet the eye in these vacuous monuments to learning.

As a profession, we have not fully realized, or really even begun to consider, the potential of newer web technologies to serve our own library-centric ends to create a more meaningful and immersive experience both in our spaces and online.

We must be committed to maintaining content-rich learning environments which are about disciplinary and cultural knowledge, not just passive “access to.” We must get beyond “discovery” and return to curated content online and in our physical spaces, even if these are presented virtually and with virtual fulfillment.

Our websites should be content-rich destinations, platforms, with calls for papers, publishing opportunities, and new books listings and faculty publications.

It should support browsing, curatorship and personalization. It should be continuously changing, along the first floor of the library. The back end of our systems should be integrated with collection management and collection development tools. It should notify us of superseded titles and new titles of interest to our community. It might recommend titles based on current usage. It should help us and our users to identify publishing trends to keep the university up to date.

The library should present opportunities for scholarly collaboration. It should also present users with academically-rigorous collections organized as collections for browsing.

We have also not considered much our power to negotiate library-friendly license agreements, or insisting upon library-centric metadata remain in the records of the ebooks we license, which could be used to create displays of new titles or titles on a certain topic.

I believe it is essential to comprehend the difference in the user experience between resource management/ discovery and collection management, and its implication or the future of libraries, the education of students, and the perpetuation of knowledge in society. We must hold tight to our ideal of collections.

Why Academic Libraries are fundamentally about Collections.

This may be hard for some people to understand, but academic libraries are not fundamentally about “access to” needed resources. Academic libraries are not repositories, either.

Libraries are about access to authoritative collections of what other people, experts in the field, think good and important to know, whether they are needed or useful to the user or not. Google cannot offer collections. ProQuest cannot offer collections. A commercial entity cannot, in good faith, offer collections. A search engine does not provide collections. Collections presuppose organization and intentionality.

Library collections are academically-rigorous bodies of disciplinary and cultural knowledge made accessible to the scholarly community as collections, meaningful and intentional organizations of knowledge consistently maintained over time. It is an intellectual construct of bibliographic content which is fundamental to academic librarianship and absolutely unique to the library as an institution. It has often been thought to be the basis for the aesthetic and intellectual experience of a library.

Collections are a way of organizing and visualizing bibliographic information. Collections are, or were, an important part of or service to the academic community. In an academic library, the collection is maintained by scholars for scholars. A collections framework guarantees accountability, integrity and academic rigor.

A “resource management” model is not a scholarly model for the academic library. It passes responsibility for title selection and inventory management to commercial vendors who profit from licensing content to libraries in bulk. But vendors do not license or maintain electronic collections, either. All they do is license and package aggregations of content. (They may call the bundles of content “electronic collections,” but there are no collection there.) To be clear, I am not saying that we shouldn’t license content from vendors, for that would be absurd.

What I am saying is that we should be careful not abandon a collections framework, and we need our systems to do more than resource “discovery.”

Subscribed content cannot at this time be arranged or evaluated as a collection in e-resource discovery systems, which is a problem for those who are charged with the responsibility of actually managing electronic collections. We cannot assemble all of the titles to which we subscribe from various sources into a coherent library collection. We could, however, if the metadata which is supposed to be in the bibliographic record (LC Classification/class number, the 050 field) were there, but it isn’t these days. That field is regarded as “optional” because it would seem to serve no functional purpose in discovery systems. Someone at Ex Libris said, “No one is going to come along and search by classification, so why is this field needed?”

Collections arranged by LC Classification are the correct overarching framework and organizing principle for the whole of the academic library, just as a curriculum should be the foundation for instruction at the university. Emphasis on collections is not my idea, something I just came up with, but what is taught in library schools everywhere, even today, as an academically rigorous model. Serial titles and e-journals, along with other resources, are part of collections–journal titles all have call numbers–but in an academic library, “resources” cannot replace “collections” as a framework without negatively impacting the quality of library services. Such is my thought on the matter.

Collection management is the difference between a professionally managed academic research library and a “learning resource center.” The experience of curated titles of the best bibliographic content, arranged according to the disciplines, is a uniquely and authentically academic library experience, a uniquely library product, where resource discovery is the experience of a search engine on an aggregation. A collection is what permits hierarchical browsing. Absent this field, there is no way to visually browse.

Without collections, what we offer is an invisible repository of searchable entitlements of dubious quality. It lacks “integrity.” There is no way to arrange all of the titles (I mean books, journals, ejournals, and ebooks) by classification, not even a report that can be generated on the backend; it isn’t just an Ex Libris issue, for OCLC’s WMS cannot do this either. A well-managed collection supports arrangement, browsing and intellectual inquiry, where discovery does not. Collections are objective and visible, ideally in the public or community eye, making a statement about what is relevant and important for educated people or those working in the discipline to know, arranged according to the priorities of the academic disciplines.

There is a qualitative difference, aesthetically and intellectually, between offering remote access to random commercial scholarly resources through a search portal and providing access to visible, curated collections of titles maintained by experts in anticipation of use and need.

We are not effective as a library being merely an invisible repository and a static website in predominantly empty spaces.

We need digital library software which displays titles according our rules for categorization and arrangement, mapped to the topics and priorities of the disciplines. We must have software which fully supports the experience of curated collections online.

I believe that librarianship as a practice is inseparable from bibliography, from the study of the published literature in a field of study or discipline, and knowledge, whether this is comprised of books or ebooks (scholarly monographs), documentaries, journals or ejournals (serial titles), peer-reviewed videos, systematic reviews, or anything else the discipline deems relevant.

It is about making this content visible, so that knowledge can become known. Many believe visibility and discoverability are the same thing. It is our function as librarians to arrange and present knowledge, and to know about publications and the discipline and to convey that to users. It is not sufficient merely to provide some mechanism for passive access to scholarly content, a “discovery tool,” but to actively facilitate and encourage user engagement with what is thought best and important to know, to raise awareness, to turn people on to new things, to help scholars reach their potential, to support life-long learning, and to educate people through creating and maintaining content-rich learning environments.

Creating and maintaining content-rich learning environments should be goal of good library design and system design.

The library should be an intellectual and cultural experience which invites exploration, independent learning and the acquisition of knowledge. Our user interfaces and physical spaces, our organizational structures and workflows, should be designed to be a stimulating, content-rich learning environment, a user experience which changes to reflect trends and publishing in real time. We should be about authoritative collections, the aesthetic and intellectual experience of our content arranged in context, not just providing passive access to subscribed resources.

Unfortunately, both titles and collections lack visibility in our digital and physical environments.

Those who possess and MLIS degree know that libraries are defined as meaningful collections of titles which represent what is thought significant and good by those working in the disciplines, purposefully maintained, arranged and displayed for the scholarly community to experience. Ultimately, library collections—”libraries”—are an important form of scholarly communication about scholarly communication.

Not only is the collection mostly or entirely gone, but people are even wondering if our catalogs are obsolete,5 because most researchers prefer to go directly to the databases to perform research there, or else use Google Scholar.

Many of the negative consequences of discovery which I write about below are not inevitable, a result of the digital revolution or the Internet, as people tend to think, nor even of discovery or search technology, but are really side effects of the the library’s over-reliance on e-resource discovery tools and vendor products to be the whole of the user experience of the academic research library. They are a result of the academic library’s commodification by vendors.

I believe the academic library must move beyond discovery and return to creating content-rich learning environments which support:

- content curation

- arrangement/browsing according to LCC

- personalization

- intellectual inquiry

- independent learning

- community engagement

It also seems to me that if taxpayer funding is to construct and fund new libraries at colleges and universities and to acquire resources, there should be business requirements for what a library at a university is expected to be and to do beyond providing its own students with wi-fi, places to sit and access to some online resources. Resource sharing must be an important part of the academic library’s mission.

Altruistic objectives such as public access and life-long learning should be hard wired into our designs. Promoting resource use should be an important part of our designs. We must have academic standards and educational and learning objectives of our own which conform to the best practices of what we are taught when we obtain an ALA-accredited master’s degree.

Collection development is still a core component of that, as is resource sharing and life-long learning.

When acquisitions in the academic research library becomes just e-resource management and discovery of proprietary content, with no collection management or any commitment to collections, and with a minimal online presence controlled by a department outside of the library, it means not that the library is going “fully digital,” nor that the library is embracing the latest technology, but that the library is divesting itself of responsibility for maintaining academic library collections, that is, for knowing about titles, for keeping up with forthcoming titles, for promoting titles, for creating metadata which allows for broad access to titles and to display, and for collaborating with faculty and others on title selection to keep them up to date.

Academic library standards have traditionally governed acquisition (collection development) policies, description (cataloging), access (circulation policies) and display (arrangement and presentation) in academic library settings.

Library standards also allow for resource sharing and system interoperability across libraries everywhere, so we could benchmark our holdings against peers and share resources with each other. Even today, despite so many academic libraries eliminating collections, ACRL Standards for Libraries in Higher Education 6 still regards collections as a core principle for libraries in higher education:

This is not the same as access to discoverable resources, which is a separate principle:

Discovery: Libraries enable users to discover information in all formats through effective use of technology and organization of knowledge.

I think it is also interesting that ACRL even defines discovery though the lens of a collection, because with discovery tools, there really is no “organization of knowledge.” The organization of knowledge presupposes the existence of a collection and metadata which supports arrangement.

If the library collection is poor, imperceptible, incapable of arrangement or nonexistent, it is likely that people will assume that the librarians who work there must not know much, regardless of their academic credentials or expertise. This hurts us and it indirectly hurts research because faculty and researchers become increasingly disconnected from trends in their field. If there is no perceptible collection, if what is on the shelves or online is completely random, disorganized, dated, or hidden, if no one is keeping up with scholarly publications in the field, why would anyone think of librarians as partners in the research process? Why would they think the librarians know anything at all? On what basis do we say a library is good? Is just providing access to databases good? Must it do more to make knowledge known?

I believe future of libraries and librarianship rides on our capacity to maintain at least the illusion of authoritative collections in some very visible form, on content curatorship, titles represented in arrangements we call “collections,” even though most of my colleagues would now dismiss collections out of hand as being obsolete.

Collections can be in any format, print or digital, but are what creates a sense of value and community around learning, education, scholarship and knowledge. Visible collections stimulates intellectual inquiry.

Collections are our industry standard, what our profession teaches are what make us good, and what academic librarianship was always about. All of our standards in the field revolve around collection management, collection development and collection display, not providing users with access to some “relevant subscription resources.”

We have no academic standard for providing relevant resources, only for authoritative collections of titles. Even if we acquire in big deals, which I think is inevitable, we still should not fundamentally be “about” vendor products, but about important publications and sources contained in the packages. Our entitlements must be capable of being displayed as a collection of titles, according to our industry standards. It isn’t that hard to accomplish with good metadata and better designed websites.

Our websites should be content-driven, authoritative and dynamic, not designed to be static entities.

Academic library collections are the closest approximation to “knowledge” and “culture” which exist in some tangible form. I do not mean just “in the library” or “on a college campus,” but all around the world. Collections, especially when aggregated, represent a kind of collective memory.

However, the widespread elimination of collections in academic libraries everywhere in 2020 represents a kind of cultural and intellectual genocide of historic proportion, as academic libraries everywhere become hollowed-out “learning centers” whose ambiguous educational outcomes cannot be differentiated from that of merely a search engine and a vacuous student center. It is cultivating ignorance and intellectual decline in higher education. The curriculum has lost its bearings and is founded in nothing. Without a collection organized by discipline and acquisition conducted in anticipation of use, there is no discipline, no there there, just various topics for searching up scholarly content. Instruction is not grounded in cultural and disciplinary knowledge. Libraries are all talking about “resource sharing,” but what they really mean is borrowing when an item is requested instead of buying. Too many libraries are doing that now, or restricting access only to their own, so the system is on the verge of collapse.

At many academic libraries, there are no collections anymore, not even digital ones, only searchable aggregations of electronic entitlements. There is an epistemological problem with this. A scholarly article presents only a single significant finding. It does not establish fact. A few articles still do not establish fact. The process through which scholarly articles, all of the discrete findings of research, are compiled and synthesized into fact often (but not always, because there are systematic reviews which are articles) involves publication quite often in a book. Books in collections often convey accepted or received opinion better than articles, the knowledge that is already known, where articles are trying to advance the field. Once books, ebooks, and collections of titles are no longer visible, we have a problem in education and the preservation of knowledge. It cannot all be articles trying to advance the field.

Many State-supported college and university libraries, such as they are, have become entirely commercially-driven and commodified. Acquisitions is about procurement, not collection development. This approach is encouraged by the design of our electronic resource discovery systems. The quality and presentation of this content, this searchable aggregation of aggregations alone, is not necessarily what is best for users. Without the framework of collections, whether by Dewey or LCC, the ability to assess the quality of our own content is limited. We do not even know what we have. Our ability to present this content to users in ways that are meaningful to them is also significantly limited.

Collectionlessness represents a decline in educational aspirations and attainment, in literacy, in libraries, in our commitment to “life-long learning,” in our ability to stimulate inquiry, and in even our belief in the capacity or even the goal of creating educated people. In these systems, titles are invisible and therefore unimportant to know.

Yet the impact of adopting a commercially-driven model is hardly discussed in critical terms in academic library literature; perhaps everyone is too afraid of going against the grain, of limiting our own already limited employment opportunities. The trend is also often unrecognized or underreported, as libraries will often use “collections” and “resources” interchangeably to conceal their collectionless status when it suits them to do so. I think we should have healthy discussion and survey users (and non-users) about the sort of library they want to have.

If we feel that collections are important, we should try to persuade library system developers to fully support them.

We say “our collection is online,” even knowing full well that there is no collection there. If it is discussed, the conversation is limited to the advantages of efficiency, convenience and access to so much through a single search interface. There are no attempts to study the impact on actual or perceived quality of library services from the perspective of those working in the disciplines, its impact on learning, and how this passive model of acquiring and providing access to random digitized content has impacted learning in the disciplines we support.

How have our more recent acquisitions patterns and workflows, largely determined by content aggregators (including our own system vendor, who is the largest academic content aggregator), impacted learning on our campuses?

I am not the only one who wants to know this, apparently, as ITHAKA, “a not-for-profit organization helping the academic community use digital technologies to preserve the scholarly record,” conducted a study a few years ago to discern how library acquisitions patterns affected use.7 It is time we revisited this on a larger scale, perhaps through ACRL surveys.

In light of these recent changes in libraries to eliminate collections, many might think my conception of a library is old-fashioned. But from my perspective, I see it as quite futuristic and visionary.

I think we can still be about the unique content-rich learning environment of a library which is meaningfully connected with the past, present and the future, and which connects people to each other. This does not mean we return to print, but on the contrary, we might seek to expand our platforms to utilize technology to better achieve our own library-centric purposes.

One example of this might be using interactive projection technology to create a more immersive experience of what is online; it might facilitate community engagement, creating new displays or titles and publications in the form of a new sort of gallery where people can communally browse a copy, watch a podcast or video about it, and download items (related books, articles or papers) to check them out (I call this “virtual fulfillment”).

We also can create virtual, browsable collections, even virtual racks of scholarly titles. If our system supported browsable collections, all that is needed is a smooth wall: current journals and titles in the disciplines can be interactively displayed in the department hallways, tap to browse. There may be a way to transform a room into a virtual stacks of the largest university library, or many libraries put together, because we all share the same metadata.

We should support content curation, even guest curation by experts.

We should support browsing in the library and online. We must be about marketing, not just vendor products but new and exciting titles. We should be about community, showcasing what faculty are researching, and promoting scholarly production by listing calls for papers and forthcoming titles on our websites.

Indeed, there are many things we can do to build intellectually stimulating environments in the library space and online to convey a sense of community value around titles, to support publishing and nourish a scholarly community (here, I mean students as well). The ideal for all libraries should be creating content-rich learning environments, not just providing passive “access to” through a search engine or empty rooms to rent by the hour.

Becoming just a search portal, vendor commodity, with our catalog becoming an inventory system of commercial database products, certainly offers many wonderful conveniences and efficiencies of scale to librarians and their users, but it is not in our best interest to have no mechanism for putting it all together to see, and for users to see what we actually have and don’t have, presented as a coherent whole. We need collection visualization capability and better support for collection management and display in our systems.

We should at least be able to present academic titles to users as any good library should, so they are is visible, browsable and authoritative within their defined scopes.

Aggregations of Resources vs. Authoritative Collections:

What is the Difference?

I believe it is not in our best interest, nor our students’ best interests, that we become just a meta-search engine, a vendor inventory system, an invisible repository of proprietary content especially as we lack a store front of our own through which to promote user engagement with titles, or through which to offer the experience of curated collections, things considered good and important for educated people to know, or interesting things our users might want to know about.

Even Spotify has playlists. At minimum, the library should be able to present core titles in a field of study.

Collection management, the hallmark of a professional librarian and the scholar, places emphasis on titles in collections, where resource management consists only entitlements, vendor products on vendor platforms, which can be retrieved by means of a central discovery index of metadata linked to documents hosted on commercial platforms. Discovery searches against this index of vendor-supplied metadata, not the contents of the articles and documents.

Different discovery engines will produce very different results.

To do comprehensive research, we all know that researchers bypass our discovery interfaces to search the databases directly. Therefore, librarians are even speculating that the library catalog is obsolete.8 If we are acquiring in a fashion where we indiscriminately acquire all content that aggregators and publishers offer in bundled packages, we could still, even maintaining this model, offer the experience of curated collections online, a layer on top of the layer, a meaningful illusion, provided that at least some of the content we buy in bulk is of sufficient quality, good metadata is there, and the system is designed to leverage the 050 field.

One of the most important technical requirements to being able to create browsable collections online is good metadata, and good metadata is being eliminated in discovery records for ebooks we receive from vendors because it would seem to serve no purpose in our systems. Library metadata, LCSH and LCC in the 050, are now being codified out of existence by vendors,4 who do not want to provide it because it is costly to produce (but not that costly; many retired catalogers would jump at the opportunity). The only purpose for the metadata they currently provide to libraries is to drive sales to libraries and researchers to their own websites for search. Making the user experience better on the library side is not their concern, but it should be ours.

Academic library collections have traditionally been mapped to the disciplines by a classification scheme, Library of Congress Classification, LCC for short, developed and maintained by librarians who possess a high level of subject expertise. This topical arrangement of titles, which many in my profession think obsolete, is not needed just to shelve books, even though this is what many seem to think (“Why do ebooks need call numbers? They don’t live on a shelf!”). Classification is needed for display and contextualization, for “collection management.” Display by classification is an important access point which was previously satisfied by going to the shelves. We all know that academic titles are only valid or authoritative only in a certain context, and the different disciplines are going to approach problems from different perspectives. What holds water in one field or specialty doesn’t necessarily in another. The broader context for a work often provides important interpretive value.

This organization or arrangement by classification is fundamental to the aesthetic and intellectual experience of the academic library, its intellectual appeal to scholars. A title’s location within this scheme is important for ensuring the visibility and contextualization of resources and for assessing a title’s relevance within a broader scholarly conversation. Context is important for interpretation and valuation. Like the arrangement of paint swatches in a store display, titles in library collections must be able to form intelligible displays of resources in an academic context for maximum intellectual and aesthetic appeal. We don’t want to be a repository, a bucket of content. The library is better than that.

Classification is unique to libraries, as opposed to commercial entities, aggregators and publishers, since publishers and booksellers use different metadata (ONIX) than we do, far less granular and nuanced. LCC reflects the structure, shared assumptions and priorities of researchers in the academic disciplines. It is not a perfect system, but this arrangement makes visible what would otherwise be imperceptible: how the discipline is organized into fields and specialties and topics, and the relevance of scholarly publications to the discipline. LCC branches off into related areas forming new branches of the ever evolving tree of knowledge. For example, Computer Science is an offshoot of Mathematics, and over the years this bough has grown new branches and buds of its own.

This tree-like conceptual scheme in which academic titles are pinned to a location relative to other items in a collection, until recently has been consistent across all academic libraries everywhere, and helped scholars to visualize their discipline and identify the gaps in their knowledge, and to a great extent, defines the discipline’s outer limits.