Contemptus Mundi:

The Original “Black Celebration” (class lecture notes)

I’ve mentioned a few times in class discussion the Contemptus Mundi tradition, going back (in this class) to our study of Augustine. It actually goes back to Stoicism, but in the Christian tradition it goes back to Augustine. It is an important theme in Medieval literature, arguably the most important. There were many poems in circulation entitled De Contemptu Mundi, On the Contempt for the World, including one written by a pope, Innocent III. It is a mystical Christian literary genre.

What it means is not really a “contempt for the world,” as in a hatred for creation, or of fellowman, but rather a spiritual or philosophical detachment, a refined indifference toward the things that most people naturally desire: wealth, glory, honors, social status, feasts, pleasures, treasure, luxury and forms of sensual indulgences of the body (the pleasures “of the flesh,” as opposed to the higher order pleasures of psyche, spirit or intellect). Contemptus Mundi is a philosophical renunciation of the fleeting pleasures of the world in favor of a more gratifying, disciplined, contemplative and intellectual life which in Christianity is associated with lasting pleasures, eternal life, and the pursuit of spiritual perfection.

The literary tradition of Contemptus Mundi was originally associated with medieval monasticism, but later on, during the Renaissance, with philosophy, study, hermeticism, insight and genius. It comes up again and again in literature, in everything from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (most definitely a contemptus mundi tale about how a seemingly perfect knight is made even more perfect by a quest in which he is led to recognize his fault, his mortality) and a more contemporary version, Hawthorne’s “The Birthmark,” a story some of you may have read in Freshman Comp. II., about a husband’s desire to perfect his already seemingly perfect wife, whose only fault is a birthmark, referred to as a tiny, barely perceptible stain. In that tale, a husband uses the magical elixirs and potions of alchemists to create gorgeous artificial worlds and a race of perfect flowers, none of which seem to last long. He seems, like Dr. Frankenstein, to wield absolute power over life and death. Then, he perfects his already seemingly perfect wife out of mortal existence by removing her birthmark through purifying potions. The astute reader will grasp that his experiment was a success, he did make her perfect, and then shortly after that, she vanishes into thin air. Did he murder her with poison, measuring out too much? Many students think so. Why then is there no body? Why is the birthmark shaped like a hand? Modern students won’t grasp the meaning or the ending of that story without an explanation of Christian dualism. They do not get how or why the flesh and temporality are imperfections, either. (What’s wrong with her flesh? Is she ugly? No, she’s human, that’s what’s wrong! The human condition is what’s wrong! Meh . . .) Outside of Christian / Augustinian interpretive framework of the Fall and Original Sin, so many of these old tales may seem to make no sense, or to make it make sense, are comprehended in such a superficial way (as misogyny, for example) as to undermine the author’s spiritual message and completely miss the point of the story.

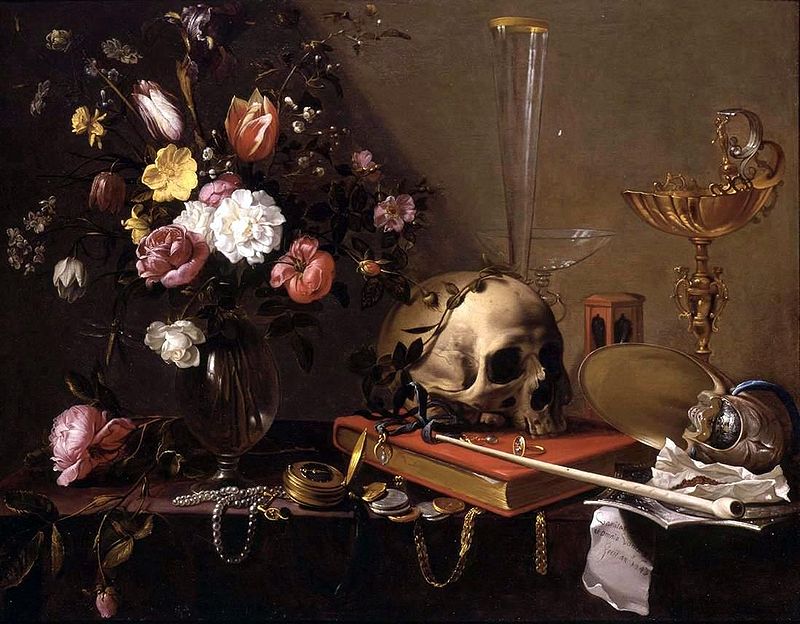

There is a corollary tradition to Contemptus Mundi in the visual arts called “Vanitas” painting, a genre of still life painting which demonstrates the concept that earthy treasure and pleasures are fleeting, ultimately pointless and unsatisfying, mere vanities (examples of Vanitas still life painting will be shown in class when we discuss Hamlet). This one, featuring a skull, is obvious, but the best vanitas / contemptus mundi still life paintings work successfully on two levels, like a good allegory.

Wikipedia defines Vanitas as “a symbolic work of art showing the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death, often contrasting symbols of wealth and symbols of ephemerality and death.” This theme may be crudely represented in iconography by piles of treasure and exotic objects covered with a thin layer of dust or a skull or crown on top (indicative of the fact that its owner is deceased). More subtle Vanitas paintings are exquisite still life paintings depicting cut flowers and other luxury objects, a pile of treasure, often in a dark (somewhat creepy) setting.

At first glance, the viewer of more subtle Vanitas paintings may not immediately notice the thin veneer of dust and decay, or that things are amiss; one is drawn in by the opulence, the detail, the eclectic and weird collection of objects, the finery, gorgeous or delicious items, the tapestries and rugs, all realistically depicted, with careful attention to surface detail to appeal to the senses. Again, the setting is usually dark, which may conceal some of the objects. Then, as you step closer and look longer, the change happens as if before your eyes: the leaves of the flowers of the bouquet on the table are slightly wilted and curled, the water in the vase is a bit cloudy, the fine porcelain has a hair thin crack, the dish is tarnished, a glass is broken, the fruit is bruised and maybe a little fuzzy. What is that snail doing there? Something is rotten just under the surface, barely perceptible. There may be a fly in the ointment or strange beetle on the table, or something in the details which spoils the picture just a bit.

Look very closely and note everything in the picture is in an oh-so-subtle state of decay and disarray, ever so slightly rotten, a fish on a serving plate with a glassy eye. Somewhere there may be a timepiece or a skull symbolizing mortality and the passing of time. Slightly wilted flowers (see also, Hamlet) are a dead giveaway you are in now the world of contemptus mundi, a twilight zone, a liminal world suspended between here today and gone tomorrow. I’ve seen one with pendulous bubbles suspended in the air as if just about to burst. Musical instruments are often put into the picture because music symbolizes the passage of time. The feast has been suddenly interrupted, a glass of wine about to tip over; the party has ended prematurely. . . also Hamlet. Fading beauty of the perfect bouquet of flowers, the temporality of all worldly pleasure and wealth, is the very point of them. So there has to be opulence and beauty to tempt you, to draw you in. It is often rich and exquisitely beautiful on the surface of things, but the experience doesn’t last long. The paintings require a double-take, the poems a re-read.

That’s what Contemptus Mundi in art and literature is about. It is my favorite genre. They are beautiful and dark. The artist gets to show off his virtuosity and skill as an artist, but also his virtue in teaching a moral lesson. When they work, they can be brilliant, because they operate on two levels, the material and the spiritual. The rubes of the world will shuffle by and say, “Oh, what a beautiful picture! I love the pretty flowers! What astonishing realism!” and never looking back. They won’t get it. These people, like Gawain’s comrades at the end of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, frivolous and well-meaning people, won’t grasp the significance of Gawain’s green sash, either, the fact that it is an outward sign of Gawain’s fallen condition and sin, “his fault,” jis attachment to this life, even though to most readers Gawain seems to be perfect (indeed, the rest of the knights laugh at him and don’t get it, saying he is being too hard on himself). Only those who perceive deeply, those with superior powers of recognition, only those who see with a more spiritual and somber eye, will discern what is really going in this world and in this story.

In most instances, Contemptus Mundi is more like an ambivalence to the things of this world, anti-materialism, a withdrawal into a kind of reflective, pensive or penitential state of being, a self-conscious or hyperconscious state (think of Hamlet), rather than actual contempt—with one exception. In literature, Contemptus Mundi is also often characterized by what we might interpret to be “misogyny,” a hatred for women, or more specifically a rejection of women as temptresses and deceivers. It is possible to read both Gawain’s speech at the end of SGGK in which he renounces women and Hamlet’s rejection of Ophelia (“Get thee to a nunnery”) as part of the medieval Contemptus Mundi tradition, because rejection of women as sexual / sensual creatures, tempters of men, is a very prominent part of that tradition. Hamlet really ought to be read as a Contemptus Mundi play. . . that is an article which needs to be written. . . maybe by me, or maybe by you?

Although Contemptus Mundi went by other names after the Reformation, and monasticism ended in Protestant lands, Puritans and Calvinists were also big on Contemptus Mundi (and Augustine, too). Milton’s companion poems L’Allegro Il Penseroso, which we will get to, contrast frivolity (the goddess Mirth) with the unseen intellectual pleasures of nun-like “Melancholy,” can also be read as a Contemptus Mundi poem. Milton, who was very religious, turns Classical pastoral genre on its head, contrasting the visceral, sensual delights of the countryside found in pastoral poems with the unseen spiritual intellectual pleasures which comes from study and contemplation of the divine. Only very attentive readers will discern who the winner of that beauty contest is between these two goddesses personifying two different lifestyles, but you must study the poems carefully to uncover their hidden meanings and see black Melancholy, the pensive nun, as a celebration of unseen pleasures which the goddess Mirth and her retinue cannot provide.