The User Experience of the New Academic Library

nitially, everyone in the library was excited and curious about this strange animal called a “new library,” and the promise of new opportunities and new roles it might bring. Like the blind man and the elephant, each of us had different hopes and expectations of what it would be like. The Library Director spoke about maker-spaces and green screens. The architects spoke of their experience and insight building new libraries elsewhere, and claimed special knowledge in constructing “learning environments.” The IT Department spoke about a building “full of technology,” and Facilities spoke about energy efficiency and building technology. I wanted to learn more about new libraries, too, for it portended the future of the profession.

nitially, everyone in the library was excited and curious about this strange animal called a “new library,” and the promise of new opportunities and new roles it might bring. Like the blind man and the elephant, each of us had different hopes and expectations of what it would be like. The Library Director spoke about maker-spaces and green screens. The architects spoke of their experience and insight building new libraries elsewhere, and claimed special knowledge in constructing “learning environments.” The IT Department spoke about a building “full of technology,” and Facilities spoke about energy efficiency and building technology. I wanted to learn more about new libraries, too, for it portended the future of the profession.

Naturally, I thought we would have an Opening Day collection (I had already developed one in Excel for a little over 100K, along with a new collection development policy better aligned with programs) and a new books display area, perhaps a leisure reading collection which we had never had.

I imagined we would have guest speakers and gallery space for traveling exhibits as well—these were high on my want list. I thought for certain we would start buying books again with a good-sized budget; I kept a wish list in my drawer, compiled by perusing back-files of Choice and NYT Book Reviews which our Serials Librarian had tossed into the recycle bin when she cancelled most print subscriptions; I carted them all back to my office. I also mined Books in Print online for the Opening Day collection. Having weeded most of the old collection of 300,000 titles, working with the faculty in the departments on that task, I felt I had some unique insight into collection gaps and where it needed to go to be better.

I never imagined 50 million dollars could be spent on a new library with no set aside for books to go into it.

The new facility took a little less than three years from conception to completion. However, for reasons I might only speculate about, the tiny library staff were hardly involved in its planning, not seen as stakeholders, so it was a surprise when we were driven over on golf carts and were permitted to enter the space for the first time. It even felt a bit sexist. The men were letting us see what would be our new home. In fact, during the public comment period, a part-time librarian colleague and I ventured to the General Facilities building to make our comments, since librarians hadn’t been asked by the architects or the Project Manager for our needs or input, which didn’t bode well. In the beginning, one afternoon, the architects with eloquent British accents spoke to the entire library staff, but it was more of a sales pitch, explaining to us their design concept based on primordial campfires, caves and watering-holes, their reference points for the design of 21st century learning environments (taken from pre-literate / oral culture, I noted, not literature culture, what libraries are about). I noticed the awkwardness of the situation, these architects lecturing us (a group of female librarians with Master’s degrees in Library Science) as to what a modern library is all about. Had I not been caught up in their romantic use of metaphor, I might have smartly asked, “Why are you building a library based on design principles inspired by pre-literature or illiterate people, and how will this new design promote literacy?” This is precisely why the architects do not invite the librarians to planning meetings.

When it all began I had assumed, just as with with any project, there would be a formal requirements document created that would identify and assess the library’s needs in sufficiently granular specificity, classifying these as “essential,” “desired,” or just “nice to have.” I have developed these technical and business requirements documents working for companies in the past. I urged the Director to create a Requirements Document for the new library, and provided her with examples and checklists I came up with from other new library construction projects and books. She responded that she was not the Project Manager for the new library and it was up to him to create a requirements document for it.

The architectural design team kept speaking about community engagement and serving the community, but never conferred with the librarians in any formal way. They also did not engage with the faculty. (I know this because I asked my Department Chair in English, who was good about keeping his ear to the ground.) It was strange, but this process of designing a building that was paid for with tax-payer money was all new to me; and I knew “the public” would be unable to use the collection because it was, for the most part, online and required current institutional affiliation to access. It was not a public library, so I do not know why solicitation of “the public” through various town hall meetings was so important for the success of this particular project. It was an academic library, after all. However, weeks later, during the public comment period, after the design was pretty much set, the Director gave us the go ahead to make our comments, and so off we went on our quest in search of a mysterious building which contained the room which contained the plans for the new library.

In a large conference room across campus, where the blueprints for the new library were spread out on a table, my colleague and I went to work adding comments to the proposed plans, a golem’s quest. The building which housed the plans seemed pretty much deserted, but we found them unattended in a conference room. We plastered the blueprints with handwritten sticky notes which we had brought with us for that purpose. I added notes like Reference doesn’t have a physical collection, and doesn’t need all these stacks, but Course Reserve does have need for shelving. Reference should be called “Research Services”—not “Reference”—and we need semi-private consultation space (not behind a solid wall where no one sees us). Also, Research Services should be close to where wherever people are actually working on papers (close to the entrance there are only directional questions). The technical processing does not need to be so spacious—there is only a Cataloger and Cataloging Assistant, and (presumably) books, if we have them, will be coming in shelf-ready. Where is our instructional classroom/presentation room? It should seat at least 50. Where are new books displayed? Where is a secure gallery /exhibit space (since we agreed that we wanted exhibit space)? Where is secure storage? Is there a loading dock? Where are the public service points on the upper floors? How do we secure the building for after-hours study? Where is my classroom/theater space? These were all things I had mentioned before to the Director who had shared the preliminary plans weeks ago with the staff. We had indeed given her our feedback to her then, but no changes had been made or seemingly passed up the ladder.

In the end, the sticky note campaign had no discernible impact. There were also things I could not have anticipated just looking at blueprints, for like most people, I have no special talent for reading them.

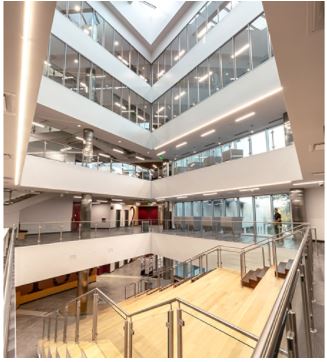

What the architects designed was a very narrow building that was mostly hollow atrium and unusable space, a six-story glass structure located on the far end of campus, very far from the colleges of Sciences and Arts, and across the street from the law school and law library. It was far from English, Journalism, Communications, Music, Journalism, Art and those disciplines (my disciplines) which had made some use of the old centrally located library, departments whose students where most likely to be readers. The building’s exterior design made a striking impression, and it had been featured in many design publications, but it was just a symbol.

The new library was empty through the center of it, with wasted or unusable space on each level centered around a hard wooden oversized bleacher-sitting staircase. The building had apparently been designed to appear tall, or as tall as it could be under the circumstances. It had a large open stairwell on one side which took up one whole side of the floor in addition to the atrium and staircase in the middle. No one used the wide stairs which took up half the building, so anything placed on that side was not seen anyway. The building was comprised of stairwells, atria, and wide hallways, unassigned offices, offices assigned to tenants not related to the library, elevators and big open restrooms. Its walls were comprised of computer-controlled electrochromic glass windows, a special reflective glass containing ionized iron capable of turning dark and dynamically blocking out the rays of the sun, with each window programmable through a cloud-based application. It was built with outdoor balconies, more unusable space, for the doors had to remain locked for safety reasons. Its thick blue-gray tinted glass window walls, glaring LED lights, narrowness, odd pipes on the ceiling and persistent hum gave it a strange vibe, like being on the inside of a tropical fish tank under artificial light. It was stagnant, unchanging, monotonous, buzzing, narrow (the shape of the floor plan) and cold, with the conduits, ducts, electrical and pipes left exposed, presumably to emphasize technology. The sound of the blower—or whatever part of the AC system it was—was like a thousand metal bbs hitting metal or the roar of a rushing river, or being under a vacuum cleaner, especially on rainy days. On my floor, the dynamic windows were set so it looked as if a storm were perpetually approaching, even on the sunniest days. There was no signage directing students to professional staff and no public service points for professional librarians out on its floors. The administrative staff was secured behind card opaque swipe doors or in invisible locations. The largest instruction room seated 24.

In retrospect, not putting doors on restrooms in a quiet space with hard, echoing surfaces was a serious design flaw. The sound of flushing, hand dryers, and more reverberated throughout each small floor. I also knew a great deal more than I wanted to about our tenants’ bathroom hygiene habits. I was on the phone one time and the person on the other end acknowledged that they could hear the flush.

It was not a cheerful space, at least not for me. It was boring and impersonal, defined by monotonous expanses of thick grey glass and cold air. It lacked intimacy. I never imagined the long-awaited new library would be like this, especially because it had recreated the exact same design defects of the old: an open empty lobby area, study rooms placed on upper floors where they could not be monitored by our tiny staff, no place to display books and no exhibit space.

The State of Texas had funded a new library, but I did not see a library there. To me, would have been preferable had they said, “the library is going to be online” and moved me into the central administrative building instead of consigning me to an outpost where I was cut off from the rest of campus. I hadn’t thought things could get worse, but somehow they did. Students weren’t coming in in sufficient numbers. They preferred the funky old, centrally located library, not this structure built on the edge of the campus with no parking for visitors. The Director continued an unpopular no food or drink policy and even during midterms and finals, which would have us and student workers patrolling looking for violators.

In short, my academic library was now gone, replaced by an over-engineered, hollowed-out architectural wasteland, with millions put toward programmable window panes—like that was going to be meaningful or inspiring to students—and other useless technology like self-check out machines and high-end security gates, but nothing for books or resources to go inside it to help the students, and no public service points. The space was echoing, empty, stagnant, lifeless, gray, vacuous, lacking academic intimacy, warmth and charm, placing no value on intellectual life or creativity. It was nothing but a vacant study hall with glass walls and a hard wooden learning staircase in the middle of it which went nowhere and nobody wanted to sit on, with a permanent art installation on half of the second floor. Why should I, a reader and intellectually curious person, like the new library? What would be the attraction for someone like me?

There was no reference / research services desk, just something called a welcome desk (for answering directional questions), which, when I had occasion to sit there, completely swallowed me up like a child wearing man’s clothes; the noise from the AC unit above me made me have to shout to be heard. The administrative offices were camouflaged behind a permanently locked card swipe utility door, quite the opposite of the inviting double glass doors and open offices in the old building which encouraged people to drop in. But after the novelty of a new building on campus wore off, even fewer people were coming into the library than before, even to complain, or to tell me they got a job, or got accepted to medical school, or were going to graduate school, or had read a good book; before, people often dropped in to see me and now, not so much. In this remote outpost, far from my academic departments, there was no way to form or maintain the relationships which had previously sustained me. Those few who came to the library silently disappeared into private and group study rooms with wheeled luggage bags in tow.

According to the American Library Association’s magazine, American Libraries, this was an award winning new library design. I pondered to myself, is this really a 21st century library?

I tried to keep an open mind for my own sanity, but it seemed to me little more than a place to sit and look out a window. It wasn’t very satisfying to work in a library without either seeing books or students. And so like that, my library was gone.

As I have come to discover, what happened to my library is actually a common occurrence, even the norm, including (an observation made by someone pursuing a doctorate in Education) the fact that the librarians are discounted or excluded from the design process for new libraries, rather than being regarded as stakeholders or subject matter experts.1 There are no post-occupancy evaluations of new libraries in library literature. New libraries continue to be built following a similar pattern, without any assessment of them as libraries, only as buildings or public spaces.

Without clear business requirements (what are we expecting the library to do) and assessment, how are we to say that these buildings are successful or not as libraries?

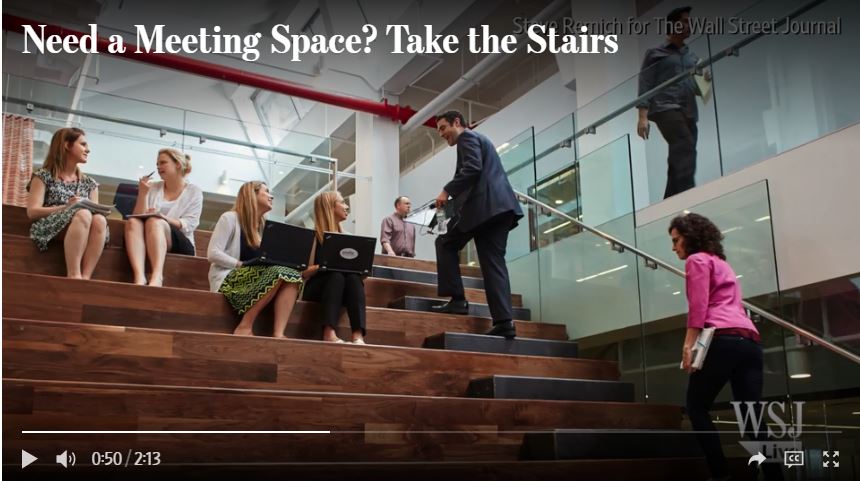

Architects claiming great insight and expertise in building learning environments, or community participation, fill up the space with large staircases, large atria, large offices and large bathrooms, because they are given no functional requirements, and also because they lack library technology to design a truly hybrid environment which integrates our digital content into the physical space. Large-stepped sitting staircases, or decorative staircases as a design element, in libraries have become a “thing”—a symbol of knowledge, learning, collaboration, sacredness and achievement rolled into one.

That my library professional association, ACRL, has abandoned prescriptive standards for libraries in favor of an approach which encourages librarians to define the library however it might please the university, even as just a collaborative study space, as long as it fits into their institutional objectives (the new measure of our success)2 is not a good trend for librarians or library users. The bottom line of ACRL’s jargon-filled “standards for libraries in higher education” are that there are no standards, we must make ourselves valuable and relevant in any way we can. These aren’t standards, but advice.

“Collaboration Facilitator” was proposed by them as a new, pre-eminent role for librarians in the 21st century.3 As a profession, if we are still a profession, I think we can do better than that.

The American Library Association has ALA accredited Master’s degrees, but there are no ALA accredited libraries. Maybe there ought to be.

If academic libraries are supposed to support “the curriculum” and “support research,” what does this really mean in the 21st century?

How does it do this without a focus on collections?

Accrediting agencies for universities have also become lax about the need for a library, and what an academic library is expected to do, even if it is online. Minimally prescriptive standards for collections have been replaced by the provision of adequate learning resources. In our case, while the outside of the building was attractive and looked like none other, inside, the new library was a cookie cutter of many other libraries built in the last few years: a central atrium, large open staircases, wide hallways, small work rooms serving no designated purpose, few visible public service points, little actual usable meeting or exhibit space, and no emphasis on books, reading or ideas.

Was this building even a library?

It did not make any attempt to raise awareness of the new, encourage knowledge of the disciplines, promote intellectual inquiry, or encourage learning. It did not maintain or display collections in the disciplines. It provided resources though subscription databases, and that was the collection. There was no collection development policy broken out by discipline, we merely acquired what vendors provided in a large subscription packages. It did nothing to encourage independent learning, or provide additional learning opportunities outside of the classroom, but assumed it was there to provide support for assignment completion.

I believe that without the ability to stimulate demand for its own resources and services through the provision of attractive, organized, authoritative browseable collections, either in print or online, the library simply cannot fulfill its academic mission.

The role of the academic librarian is to create content-rich learning environments (“libraries”) that stimulate scholarship, cultivate knowledge and inspire creativity.

With new academic libraries, the more impressive the space, the more conspicuous is the absence of books, whose cost pales in comparison to the technology, empty space (for things like monumental learning staircases), and the commodified packages of aggregated content the new library typically provides.

Scholars and intellectuals, the sorts of people who are generally found on college campuses, have no interest in visiting or spending time in empty spaces. Educated people and scholars care about books, content, culture, media, and especially knowing what other educated people know and are writing / thinking about. Even if they don’t care about reading physical books per se, they care about the ideas in the books.

They want the library to turn them on to new things and new thoughts. We are supposed to be keeping them up to date.

That is the library experience people value, not empty spaces.

Whether usage would have dropped at my library regardless of efforts to revitalize the collection through an Opening Day collection featuring new books with jackets dressed up in Mylar, attractive displays and exhibits, leisure reading, sponsor a book program (so people could put their name on a book plate and feel they have achieved immortality), current materials targeted more to the interests of undergraduates, and creative ways to display ebooks in the physical space, coupled with programming—fun things like Bob Ross nights and “tell us about your research” night—is a question no one can answer, but my own opinion is “yes.”

It was at least worth a try.

I wanted to display ebooks in the space to encourage use. (I also wanted to simulcast and stream college games in the library.) Online, I wanted to showcase outstanding student work in our library’s digital repository so parents could google their child’s name and see a paper they had written at school, and this might possibly help that student land their first job after graduation. I wanted art exhibits and Research Week poster sessions to bring the place to life.

I had hoped to display student art and writing in the library space. I wanted musical performances from the Music department, video shorts from Communications, and a way to bring people together. It was an HBCU, so I definitely wanted to showcase the best black literature, authors, artists and intellectuals. I wanted to create a vibrant place for community and culture to thrive.

For a medium-sized campus library with large numbers of undergraduates and graduate students on campus, the presence of new books in the library, attractively displayed, would have contributed to the creation of a stimulating and educational learning environment.

It would have made the library more interesting and appealing to students, even as a place to study.

- Stewart, Christopher. The Academic Library Building in the Digital Age: A Study of New Library Construction and Planning, Design, and use of New Library Space, University of Pennsylvania, Ann Arbor, 2009. ProQuest, http://tsuhhelweb.tsu.edu:2048/login?url=https://tsuhhelweb.tsu.edu:2084/docview/304980905?accountid=7093. ↩

- “Standards for Libraries in Higher Education,” American Library Association, August 29, 2006. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/standardslibraries ↩

- Association of College and Research Libraries. “Connect, Collaborate, and Communicate: A Report from the Value of Academic Libraries Summits.” Prepared by Karen Brown and Kara J. Malenfant. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries, 2012, p. 16. http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/value/val_summit.pdf ↩

“Religion in the Academy (First Things, 1994). An excerpt of a letter to Dr. George Marsden, Professor of History at the University of Notre Dame, written while I was a graduate student at Indiana University. He submitted the letter for publication to First Things, which resulted in my being interviewed by The Chronicle of Higher Education. In 1997, this letter and my experience was discussed in the book, Religious Advocacy and American History.

“Religion in the Academy (First Things, 1994). An excerpt of a letter to Dr. George Marsden, Professor of History at the University of Notre Dame, written while I was a graduate student at Indiana University. He submitted the letter for publication to First Things, which resulted in my being interviewed by The Chronicle of Higher Education. In 1997, this letter and my experience was discussed in the book, Religious Advocacy and American History.